If you spend most of your day in front of a computer, you probably already know how tricky it can be to keep blood sugar steady. Even with careful meal planning, numbers can creep up while you’re sitting through back-to-back emails or long meetings. It’s not always the food that’s the culprit – often, it’s the hours of sitting still.

That’s where “micro-moves” come in. Small, simple bursts of activity woven into your workday can help muscles use glucose more effectively and smooth out the highs you see on your CGM. Best of all, they don’t require a gym bag or a lunch break workout.

Disclaimer: This article is for education only. It is not medical advice. Always follow your healthcare team’s recommendations before making changes to your diabetes routine.

Why sitting still pushes numbers up

Think about what happens after lunch. You eat, walk back to your desk, sit down, and before you know it, your CGM is showing a slow, steady climb. That’s because when muscles stay inactive, they aren’t pulling glucose from the bloodstream as efficiently (Dempsey et al., 2016). The body leans more heavily on insulin, which can make post-meal spikes harder to manage.

People with diabetes often notice:

- Glucose spikes are sharper after eating at the desk

- Readings creep up during long, sedentary afternoons

- It takes extra effort – more walking or correction doses – to bring numbers back down

It’s not just frustrating; it’s distracting. But breaking up long stretches of sitting with short bouts of movement helps muscles “wake up” and get back to work.

Micro-moves you can do at work

Micro-moves are exactly what they sound like – tiny bursts of activity that fit easily into an office routine. The point isn’t intensity, but frequency. Even a couple of minutes of movement can give glucose a place to go.

|

Micro-move |

How to do it |

Why it helps |

|

Seated marches |

Lift knees alternately for 1–2 minutes under your desk |

Keeps blood moving and activates leg muscles |

|

Chair squats |

Stand up and sit down slowly 8–10 times |

Uses large muscle groups that draw in glucose |

|

Corridor laps |

Take a walk around your office floor after finishing a task |

Adds steps without disrupting workflow |

|

Standing stretches |

Reach overhead, roll shoulders, rise onto tiptoes |

Boosts circulation and eases stiffness |

|

Printer push-ups |

Hands on desk or wall, lean in and push away 10 times |

Engages upper body and raises heart rate slightly |

These moves don’t need to draw attention – you can do most quietly at your desk. Over a full workday, they add up to meaningful activity your muscles (and glucose levels) will thank you for.

How often is enough?

Studies show that standing or moving for even one or two minutes every 30 minutes makes a difference to glucose and insulin responses after meals (Thosar et al., 2015). If 30 minutes feels unrealistic, aim for once an hour to start.

A few easy tricks:

- Stand when you take phone calls

- Walk the long way to refill your water bottle

- Set a calendar reminder that nudges you up every 45 minutes

It’s not about perfection, but consistency. The more often you move, the more predictable your glucose patterns can become.

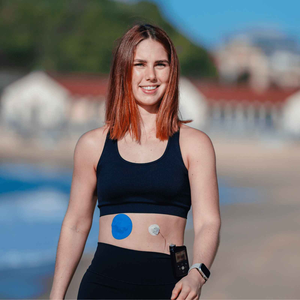

Keeping your CGM secure through the day

Of course, more movement also means more chance of friction on your CGM patch. Office clothing, heat from sitting, or just constant shifting in your chair can loosen adhesives. Nothing interrupts your day like a patch peeling halfway through a meeting.

That’s why many people choose breathable CGM patches to give their sensors extra security at work. Options like Dexcom G7 patches or Medtronic Guardian patches are designed to move with you while resisting edge lift. For extra support, especially if your office tends to run warm, adhesive wipes can help your patch stay put without irritation.

If you’re wondering how to make your patches last the full wear time, you can check our guide on proper skin prep.

People also ask

Does sitting at a desk raise blood sugar?

Yes. Long periods of sitting slow muscle activity, which means less glucose is pulled from the bloodstream and post-meal highs last longer.

What exercise is best for office workers with diabetes?

It doesn’t need to be formal exercise – short, light moves like stretches, walking to the kitchen, or desk squats can all help.

Can a few minutes really make a difference?

Yes. Even two minutes of light movement every half hour can support lower glucose levels compared with uninterrupted sitting.

How do I stop my CGM patch from peeling during the day?

Reliable CGM patches, good skin prep, and adhesive wipes can reduce friction and edge lift during office routines.

Building a workday that works for you

Managing diabetes during office hours isn’t about big, dramatic changes – it’s about the little things you repeat day after day. Micro-moves are easy to build into your routine and, over time, they can make your glucose readings more stable. Combined with the right CGM patches to keep your sensor secure, you can move through your workday with confidence.

So the next time you notice your CGM creeping upward mid-afternoon, don’t think you need a workout to fix it. Sometimes, all it takes is standing up, stretching, or walking the long way to the printer. Those small moves count – and they keep your sugar steadier than you might expect.

References

Dempsey, P.C., Larsen, R.N., Sethi, P., Sacre, J.W., Straznicky, N.E., Cohen, N.D., Cerin, E., Lambert, G.W., Owen, N., Kingwell, B.A. and Dunstan, D.W. (2016). Benefits for Type 2 Diabetes of Interrupting Prolonged Sitting With Brief Bouts of Light Walking or Simple Resistance Activities. Diabetes Care, 39(6), pp.964-972. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2337/dc15-2336

Thosar, S.S., Bielko, S.L., Mather, K.J., Johnston, J.D. and Wallace, J.P. (2015). Effect of prolonged sitting and breaks in sitting time on endothelial function. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 47(4), pp.843-849. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000479